Reformation Series: John Knox

Introduction

Good morning. I missed you last Sunday. But today I am saddened to share that Mildred Flanary, a remarkable woman who inspired so many of us, passed away yesterday at the age of 104. Let us keep her family in our prayers during this time.

John Knox: The Father of the Scottish Reformation

In my last sermon, we explored the life and influence of John Calvin. Today, we turn to one of his most devoted followers, John Knox—a towering figure in the Christian Church and a leading force in the Reformed tradition. Often hailed as the father of the Scottish Reformation, Knox’s life was defined by a fervent faith, powerful preaching, and an unwavering dedication to the principles of the Protestant movement. His legacy endures in the Presbyterian Church, continuing to shape Christian thought and practice even today.Early Life and Education

Born around 1514 near Haddington, a small town east of Edinburgh, Scotland, John Knox came from humble beginnings. Little is known about his early life, but it is believed that he was educated at the University of St. Andrews or possibly the University of Glasgow. His studies likely included theology, philosophy, and perhaps law, providing a strong foundation for his future work. He was ordained as a Catholic priest around 1536. However, the seeds of change were already being sown across Europe. The Protestant Reformation, sparked by figures like Luther and Zwingli, was challenging the doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church. Scotland, too, was beginning to feel the stirrings of reform.

Conversion to Protestantism

The turning point in his life came through his association with George Wishart, a Scottish reformer who preached Protestant doctrines. Knox became his bodyguard, carrying a two-handed sword to protect him. In 1546, Wishart was arrested and executed for heresy on the orders of Cardinal David Beaton. This event profoundly impacted Knox, solidifying his break with the Catholic Church. Following Wishart’s death, a group of Protestant nobles assassinated Cardinal Beaton and took refuge in St. Andrews Castle. Knox joined them in 1547, where he began preaching openly, marking the start of his public ministry. His sermons emphasised the authority of Scripture and critiqued the abuses within the Catholic Church.

Captivity and Exile

Later in 1547, French forces captured St. Andrews Castle, and Knox, along with others, was taken prisoner. He spent 19 months as a galley slave on French ships—a period of hardship that tested but did not break his resolve. Released in 1549, he went to England, where the Protestant Edward VI reigned. In England, his reputation as a fiery preacher grew. He served as a royal chaplain and was offered positions in London and Newcastle. However, the ascension of Mary Tudor (Mary I) to the throne in 1553, who sought to restore Catholicism in England, forced Knox to flee to the European continent.

Knox found refuge in Geneva, Switzerland, where he met John Calvin. Geneva was a hub of Reformed theology, and Calvin’s ideas deeply influenced Knox. He absorbed Calvin’s teachings on church governance, the sovereignty of God, and the importance of a disciplined, moral society. Most, if not all, of the Presbyterian polity came from Calvin. During this time, Knox also pastored an English-speaking congregation in Frankfurt, Germany. Conflicts over worship practices led him back to Geneva, where he continued to refine his theological views and pastoral skills.

Return to Scotland and the Reformation

In 1559, after years of exile, Knox returned to Scotland. The country was ripe for reform. The Protestant nobility, known as the Lords of the Congregation, opposed the regency of Mary of Guise, a staunch Catholic and mother to Mary, Queen of Scots. Knox became the leading voice of the Reformation in Scotland. His preaching was passionate and direct, calling for the establishment of a church based solely on biblical principles. He criticised idolatry and the Mass, urging the removal of Catholic practices. His efforts culminated in the Scottish Parliament’s adoption of the Confession of Faith in 1560, effectively establishing Protestantism as the national religion. The First Book of Discipline, largely authored by Knox, laid out the organisational structure of the new church, emphasising education, moral discipline, and the administration of sacraments according to Reformed theology.

Conflict with Mary, Queen of Scots

One of the most dramatic episodes in his life was his confrontation with Mary, Queen of Scots, who returned from France in 1561 to claim her throne. A devout Catholic, Mary represented a significant challenge to the Protestant establishment. Knox had several meetings with the Queen, where he did not shy away from expressing his views. He admonished her attendance at Mass and warned of the dangers of idolatry. Their encounters were tense, marked by stark theological disagreements and personal animosity. His uncompromising stance made him both a revered and controversial figure. While many admired his courage and conviction, others saw him as obstinate and harsh, particularly in his dealings with the Queen.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Knox continued to preach and write. His most significant literary work, “The History of the Reformation in Scotland,” provides a detailed account of the Scottish Reformation from his perspective. It remains a valuable historical resource, though it reflects his biases and the polemical style of the time. His health began to decline in the late 1560s. Despite physical weakness, he remained active in ministry until his death on November 24th, 1572. His funeral was attended by many who recognised his profound impact on Scotland’s religious landscape.

His influence extended beyond his lifetime. He is credited with establishing Presbyterianism in Scotland, characterised by a system of church governance led by elders (presbyters) rather than bishops. This model emphasised collective leadership and accountability to Scripture. His advocacy for education led to the establishment of schools and universities, promoting literacy and learning among the general population. Knox believed that everyone should be able to read the Bible for themselves, a radical idea at the time when the Catholic church executed any non-clergy who either owns or reads the Bible. His ideas also had a broader political impact. His writings on resisting ungodly rulers contributed to developing theories about the rights of citizens to hold their leaders accountable—a precursor to modern democratic thought. And his teachings of resisting ungodly rulers influenced the Presbyterian preachers in the British colonies, especially in the North America.

John Knox was a man of his time—zealous, confrontational, and deeply committed to his understanding of God’s truth. While some criticise his harshness and intolerance, especially towards Catholics and women in authority, others celebrate his courage and steadfastness in the face of opposition. His life challenges us to consider the cost of discipleship and the importance of standing firm in our convictions. His dedication to the authority of Scripture, the purity of worship, and the moral integrity of the church continues to inspire believers today.

Similarity between Presbyterians and the US

As announced, we will hold a called congregational meeting on Sunday, December 15th to elect new elders who will serve on the session for a three-year term. This process is part of Presbyterian polity, established by John Calvin and formalised by John Knox. Let me take a moment to explain the Presbyterian structure. In Presbyterian governance, each congregation elects its own elders, who form the governing body of the church, known as the session. Regional groups of elders gather to form a Presbytery. Several presbyteries unite to form a Synod—there are 16 Synods in total—and at the very top, we have the General Assembly, which serves as the national council. While the General Assembly sets overarching guidelines, each Presbytery retains sovereignty and autonomy, operating within those guidelines. This structure mirrors the structure of the United States government, with the federal government at the top, followed by states, counties, and local municipalities. Just as each Presbytery has its own level of sovereignty within the Presbyterian Church, each state in the U.S. has its own sovereignty within the federal system.

The elders on the session are elected by the church members—they are representatives of the congregation, not appointed by the pastor. Similarly, members of Congress are elected to represent the citizens and make decisions on their behalf. In our church, we have an even number of elders on the session, although many Presbyterian churches prefer an odd number to avoid ties in voting. Generally, the pastor, who moderates the session, does not vote; however, if there is a tie, the pastor may break it. This arrangement likely sounds familiar, as it resembles the U.S. Senate, where 100 senators vote, and in the case of a tie, the Vice President casts the deciding vote. The similarities between the U.S. government structure and Presbyterian polity are numerous. Is this merely a coincidence? Not at all. Presbyterians played a significant role in the founding and shaping of this nation, and thus the American system reflects values deeply embedded in our Presbyterian Church.

Presbyterians Shaping the US

Many Presbyterian preachers in the colonial era were part of the so-called Black Robe Regiment—a group of clergy who through their sermons inspired and encouraged the colonists to fight for independence. They provided moral and religious justification for resistance, framing the struggle as a righteous cause against oppression. Their preaching was fearless, bold, and direct just like John Knox, even as they faced severe persecution from colonial authorities. Some British governors went so far as to issue edicts banning all Presbyterian preachers from their territories. The influence extended beyond the pulpit; many Presbyterians were actively involved in the fight for independence, and British officials often referred to the American Revolution as the “Presbyterian Rebellion.” Among the signers of the Declaration of Independence was John Witherspoon, a Presbyterian minister and the only clergyman to sign the document. Witherspoon also founded Princeton University, one of the nation’s oldest institutions of higher learning, and personally mentored many future American leaders, including James Madison. His influence shaped generations of leaders who helped mould the young nation, grounding its institutions in Presbyterian principles.

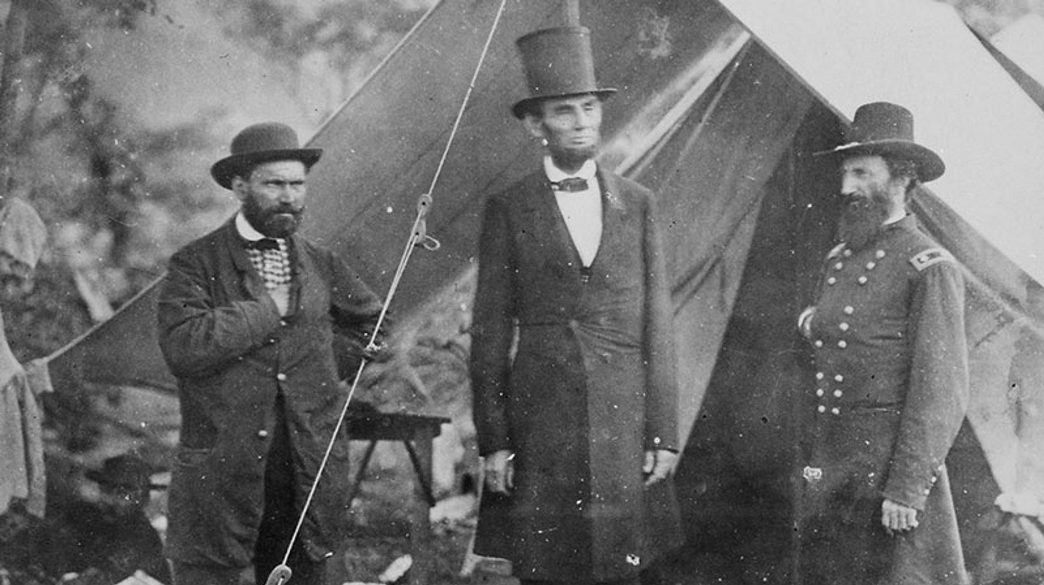

Presbyterians continued to shape the United States across various areas of governance and philosophy. They were among the earliest advocates for the separation of church and state, championing religious liberty and opposing state-sponsored churches. They also promoted pluralism and tolerance, often collaborating with other denominations, including Baptists, Quakers, and even Catholics. Another notable Presbyterian influence is Abraham Lincoln. While he never formally declared himself a Presbyterian, he regularly attended Presbyterian churches throughout his life, including the First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, IL, and New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. Lincoln’s legacy remains a pillar in American history, and his moral and political impact is felt even today. Alongside and before Lincoln, many early Presbyterians championed abolition, arguing that slavery was incompatible with Christian teachings. Presbyterians also established charitable organisations, schools, hospitals, and missions to address social needs, engaging deeply with their local communities, which tradition we still follow in this very town of Lebanon.

The role of Presbyterians in the founding and shaping of this nation is a vast subject, one that could fill an entire year’s study in college. Briefly, however, Presbyterians made a profound impact on the United States through their contributions to political thought, education, social reform, and religious freedom. Their principles of representative governance, commitment to education, and advocacy for liberty and justice helped lay the groundwork for American democracy. The active participation of Presbyterian leaders and congregations in the Revolutionary War and in the formation of national institutions left an enduring legacy that continues to shape American values and structures today.

You Should Vote

As I mentioned earlier, Presbyterian preachers once inspired and encouraged people in this land to stand up, take up arms, and fight for this nation’s independence. Today, as a Presbyterian preacher, I encourage you to do the same, to fight—but not with rifles, rather with your ballots. Thanks to the groundwork laid by Presbyterians in the early days, we now have a democratic system in which we can make our voices heard peacefully through voting and healthy debate. This system, rooted in the principles of Presbyterian governance, ultimately traces back to John Knox, who founded Presbyterianism in Scotland and championed representative leadership. Through voting, we honour that legacy and continue to shape our nation with faith and conviction. So please vote, it is this coming Tuesday.

Conclusion

As we reflect on the life of John Knox, we see a vivid example of how one person’s faith and determination can shape the course of history. His contributions to the Reformation transformed not only Scotland but also influenced the founding principles of the United States, and left an indelible mark on the global Christian community. His story encourages us to engage deeply with our faith, to seek truth earnestly, and to live out our convictions with passion and integrity. May his legacy spur us on in our own journey of faith, as we seek to honour God in all we do. I don’t usually end sermons this way, but today I’ll close with, “God Bless America.” Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment